The pigeon was standing outside the exterior lobby doors when I left my studio on Wednesday. It caught me off guard to see the bird, essentially blocking my exit to the elevator. I stepped forward, assuming it would fly—or, at the very least, bird-walk its way in the opposite direction. It didn’t. Shoo, I waved my wrists gently, then clucked a little like I do when my cats are underfoot at home. The bird just stared at me.

It was then that I noticed a disconcerting thing—hairless, with spindly legs and a milky-yellow hue. Large, but alien enough that, at first, I worried it was a baby pigeon. I returned to my studio and sat back down at my desk. I googled, “baby pigeon look like?” Whatever was crawling around next to the bird looked nothing like the images on the screen. I shut down the computer and locked up the studio for a second time.

There are countless exits in the building on each floor—stairs and multiple freight elevators, one of which was next to the lobby exit. I hit the call button on the freight elevator and stepped inside, never taking my eyes off the pigeon, who stood motionless except for the rapid blinking of its black eyes.

The next morning, I exited the passenger elevator, stood inside the lobby, and felt relieved to not see the pigeon through the glass doors where I had left it the night before. I did see clumps of rice scattered outside on the landing. I stepped through the door and immediately noticed the pigeon, to my left, standing in front of the freight elevator.

Shit.

Literally, shit, everywhere. I’m not a bird expert, but something was wrong.

I went inside my studio and researched what to do with a pigeon that was hurt or acting strangely. I filled out a digital intake form for a local animal rescue—a process that requested video and photo evidence—and hit submit. I dug through my bag and found a Tupperware of almonds, dumped it into another container with my sandwich, and filled the first Tupperware with water.

The pigeon could walk, and I couldn’t see any noticeable injury. No blood, no bone. I placed the container of water next to the elevator and returned to my lunch bag for the almonds, which I crushed using the plastic top. I scattered a handful of the crumbs on the ground near the bird and cooed.

Within a few hours, I received a reply from the wildlife rescue, though I didn’t feel hopeful that the pigeon would be a priority, given that it wasn’t doing anything besides sitting there. The volunteer I spoke to agreed that it was unusual behaviour and suggested that the video and photo I’d sent indicated domesticity—perhaps it was lost. Or egg-bound.

In my early twenties, I’d owned a small lovebird, who my girlfriend at the time had wanted very badly, to keep her company while I was on tour. Having not grown up with birds, I found the cage, and the impossibility of flight, to be an awfully sad life for an animal with wings. We called him Nicholas Cage—Nic, for short. When I wasn’t touring, and my girlfriend was at work, I’d often let Nic out of his cage, and he’d flutter from window frame to my head, back to a piece of furniture or door handle, letting out jets of shit as he went.

We’d had him only a few weeks when I found him in distress at the bottom of the cage, shuddering, his feathers mussed with static electricity. The pet shop had no advice, so we covered his cage with a towel and went to bed. In the morning, Nic was back in his usual spot on a perch, and at the bottom of the cage, a single bloodied egg. Nic was a girl. The egg was not fertilized, and after a period we deemed respectful, we removed the egg and cleaned the cage. After we broke up, my ex sent me an email letting me know Nic had died. She’d buried him at the beach near the apartment.

I hoped the pigeon wasn’t egg-bound. I allowed myself some optimism. The bird was lost, but it would work up the courage to venture from this spot eventually. Right?

All day I worked at my desk, though the bird never left my mind. I’d periodically step outside to check on it. On one of my visits, the bird had laid down, its feet tucked under its body. Like a chicken, or Mickey, my cat, whom we describe as looking like a loaf of bread in a similar position. Did this mean the bird was comfortable? At ease? Or dying?

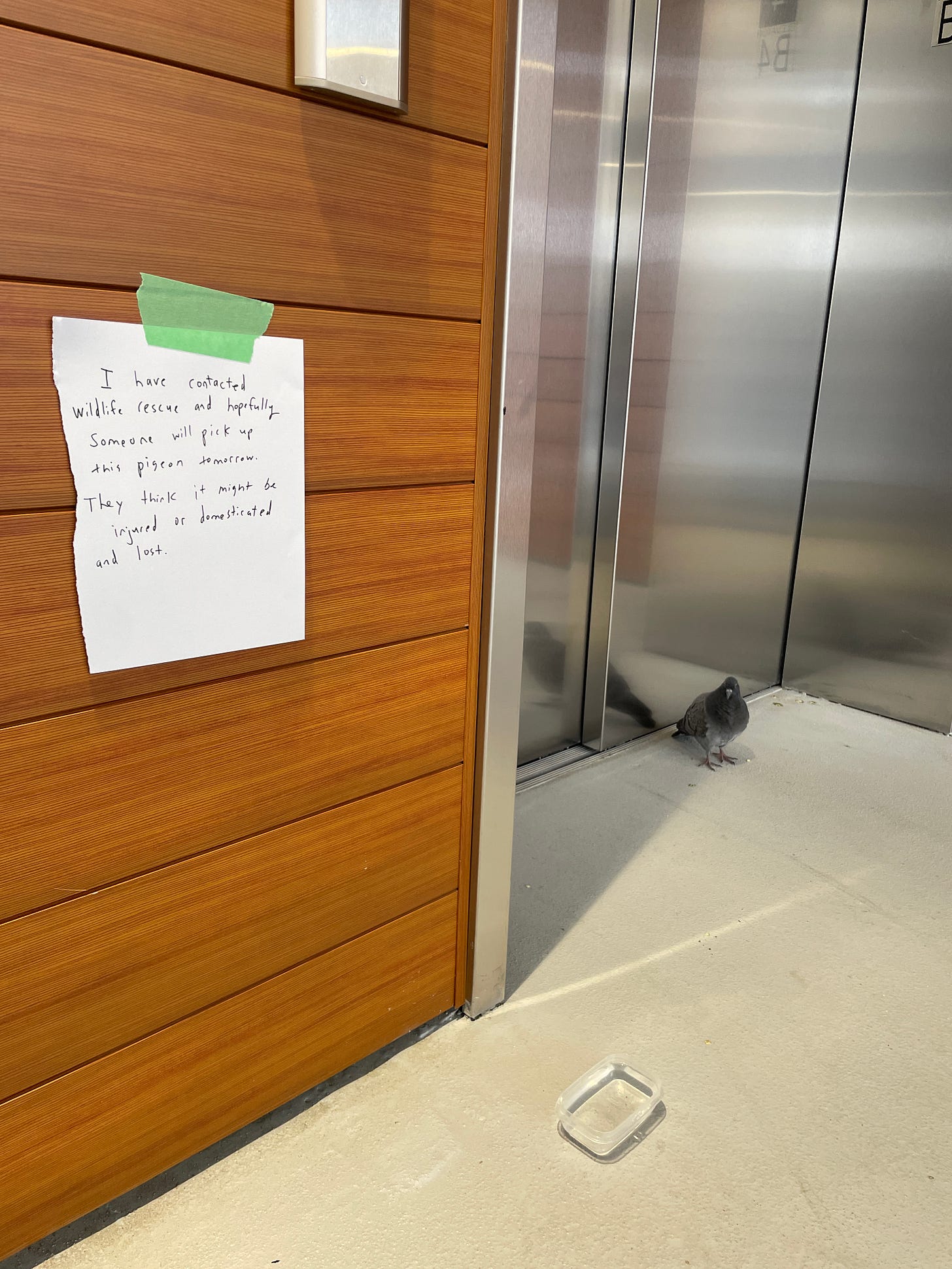

I called Stacy and begged her to pick up bird food. I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving the pigeon for another night with nothing to eat. When she arrived, I tried not to read the look on her face, because I knew this all seemed ridiculous. We sprinkled millet and sunflower seed on the ground. I wrote out a sign and taped it to the elevator door, explaining that someone would be coming to get the pigeon. It was domesticated. Lost. The pigeon pecked at the food on the ground. It tucked one of its feet up into its body—like a pelican. Goodnight, bird.

This summer, a family of owls have made the streets around our house their hunting ground. Crowds of people gather on the sidewalks, heads tilted up to the sky, searching the branches and leaves for hours as the owls and crows swoop, caw, and fight. Photographers with long-lensed cameras, like a horde of paparazzi stalking a celebrity, snap away. A neighbor told me the owls tipped a crow’s nest into the street and ate the babies. Another sent a photo of one of the owlets sitting on a neighbor’s fence outside their chicken coop. Yesterday, Sid nearly picked up a curious object outside our house—it was a black rat’s tail and a spinal cord picked clean of meat with a tuft of fur still attached.

Do I root for the owls because they’re a rare sight? And let’s be honest—they’re better looking than the crows. Or a pigeon. The pigeon’s feathers are the same grey, with a slightly purple tint, as our Scottish Fold cat, Holiday. The owls’ moon-shaped faces and their amber eyes make me think of Holiday, also. Holiday with wings.

The next morning at the studio, the pigeon was still camped out in front of the freight elevator, and it seemed to greet me with a familiar recognition. I no longer believed a volunteer would come for my pigeon, so I emptied out a small box and poked holes in the top with a screwdriver. I dug through my storage bins and found a set of towels, one of which I spread out at the bottom of the box, the other I hung around my neck. I went out to the vestibule—guilty—slowly, placed the box next to the elevator, and began my attempt to capture the bird.

I got lucky the first time, and the towel covered the bird as it squeaked—the first sounds I’d heard come from it in days. I crouched, my hands reaching for the flapping lump. It broke free and flew over my head, fluttering more than flying, I guess. We spent the next 20 minutes doing a version of this choreography. I became more hesitant. I was afraid the bird would attempt to fly off the landing and fall the many stories to the pavement below. It didn’t seem to be able to maintain flight for long.

I went back to the studio and dug out a sheet from a vacuum-sealed bag of bedding. I hesitated, imagining a future where I might use this sheet again, for a human guest. It was the best shot I had, so I bunched it up and stalked back out to the elevator. I stood watching the pigeon—its little throat and mouth were vibrating. I was afraid I would give it a heart attack. Finally, I stepped forward and threw the sheet like a large net over top of the bird, picked it up, and placed the lump of its body into the box. I put the lid gently on top, pulling the sheet out slowly and heard the pigeon’s wings brushing frantically on the sides of the box. The lid was on. I taped it down.

I took the bird down the elevator to my car, placed it in the back seat, and brought up the driving instructions on my GPS. I was most concerned it would be too warm in the box, but also, I didn’t want the bird to escape inside the car. I’m haunted by news stories of people dying in traffic accidents because of loose animals distracting them. You’d be amazed at how often that sort of thing happens.

I turned the speakers to play my podcast only out of the front, to not bombard the bird with sound. I drove carefully, slowly, out to Burnaby. At the rescue sanctuary, I felt like I was no longer in the city. It was a wooded, car-free hideaway inside a large park. I placed the box with the pigeon in the intake shed and filled out a form. The volunteer told me they’d assess the bird’s health and, if it was fine, they’d release it back where I’d found it.

Please don’t do that, I begged him. This is so much nicer than where I found him. Can’t it just be released into the park?

That’s not how it works, he told me.

I drove back to the city feeling melancholy, thinking about a pigeon that had once made a nest on the balcony of one of my apartments in Montreal. At first, it seemed exciting—like watching a nature show but up close. The bird brought scraps of garbage, twigs, leaves, and built itself a nest. Then a friend told me that pigeons often carry fleas or worse. I became obsessed with the idea that our home would become infested. No egg had been laid, and one afternoon, I went out on the deck and destroyed the nest. I waited, and when the pigeon returned to find its nest gone, I felt ashamed and sick about what I’d done.

-Sara

Share this post